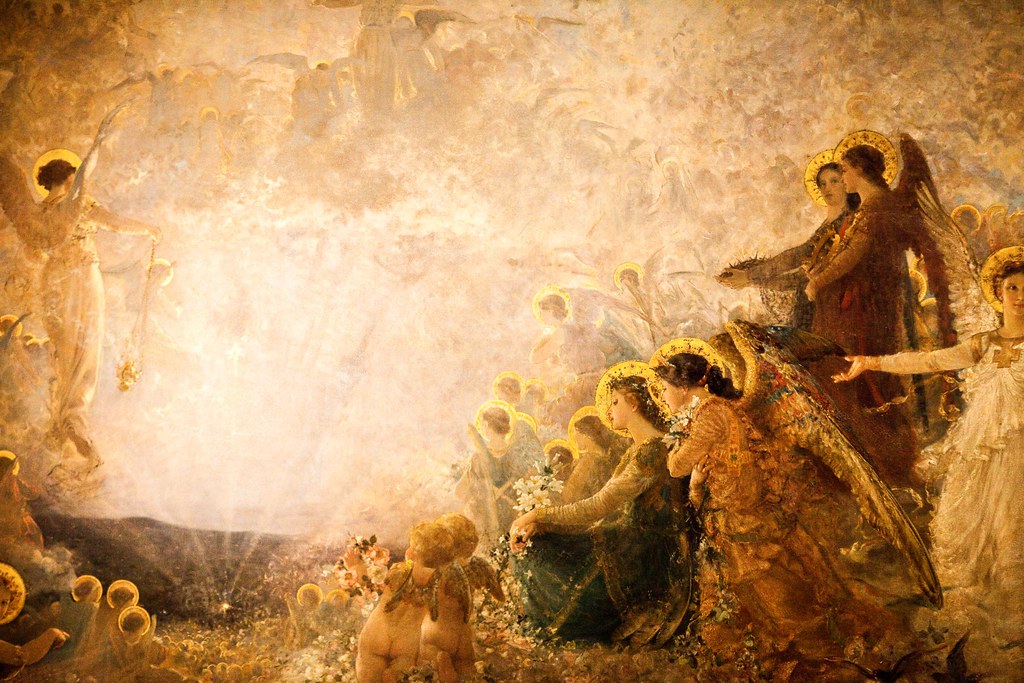

When I first saw this painting a few years ago at the Brooks Museum,

I thought it was amazingly beautiful.

It's huge (over 6.5 x 9.5 feet) and splendid, so you can't walk by without stopping to look.

(It is so large, it is hard to find a full copy of it on the Internet. The first I've posted, which comes from this lovely blog, has the whole painting; the second has better lighting but not the whole thing.)

And when I stopped and looked, I saw the title was "Light of the Incarnation."

Only then was I able to see that (almost) all the angels are looking down, way down,

to the source of light in the left-hand lower corner.

And then the painting began to say more and more, beyond

"There's a bunch of beautiful angelic figures in lovely lighting."

It brought to mind the words from Luke's gospel, after one angel had appeared to the shepherds,

announcing the birth of a baby who was a Savior.

And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavnly host

praising God and saying,

"Glory to God in the highest,

and on earth peace among men with whom he is pleased!"

It brought to mind from John's gospel, "The light shines in the darkness,

and the darkness has not comprehended it."

And that fascinating passage in I Peter,

"It was revealed to them that they were serving not themselves, but you,

in the things which have now been announced to you by those

who preached the good news to you through the Holy Spirit sent from heaven,

things into which angels long to look."

And then, looking longer at the painting, I saw that

a crown of thorns is held out by one angel, symbolizing the crucifixion;

and a golden crown, symbolizing victory.

and lilies are held by another, symbolizing the resurrection;

and incense by another, symbolizing prayers and the holiness of the event.

(At least I think that's what it is....)

These symbols are powerful, representing the whole story to come,

set in motion long before the moment captured by the painting.

But I think the most powerful part for me when I've seen it is simply that you can't

look anywhere without seeing angelic forms. They fade in and out as you stand and look.

(Take time to enlarge the photo and look at it closely so you can see them.)

Granted, they are more representative of beautiful women with wings than they are of

the angels described in scripture, in those few places where they are described.

But even in this romanticized form, they serve an important purpose.

We so easily fall into thinking that only what we can see or hear or taste or touch is real,

which our own scientific approach should warn us about, since before the magnifying glass,

many things that were not known by the senses were very much real, both making life possible (oxygen) and killing people (bacteria, germs, etc.)

The fact that we did eventually develop magnifying glasses, telescopes,

and all kinds of technologies that have expanded our ability to know things through our senses,

doesn't assure that we will be able to do that for every reality that exists.

And when I read things written by those who lived before all these technologies--

those who had access to all kinds of spiritual and philosophical writing,

but not to what we today consider scientific writing--

I often think that they saw and understood more than we do today.

They knew so much about life and love, humanity and hope, purpose and peace.

Some today may laugh at them for believing in angels.

But we really don't know who will have the last laugh, do we?

I only hope it will be laughter of joyful goodness, not the cynical laughter of "See, I was right."

The very word "Incarnation,"

signifying that something that was not made of flesh is being made into flesh,

assumes that there are realities beyond what we can experience in a purely fleshly way,

through those five senses we are taught to identify and name in elementary school.

It assumes a realm that is more than flesh, or beyond flesh,

a realm that can inhabit flesh at will but is not limited to it.

The new quotation under the title of my blog comes from a man who writes often about the realness of the realm that we cannot see with our eyes in the way we think we'd like to.

And here another author

shares the story of a man who seems to have had the ability to see angels. The story of his life seems to indicate that perhaps we have lost the ability to see some things

by the way we have focused so intensely on seeing certain things in certain ways,

and creating strong rules about what is possible and what is not possible.

I urge you to take the time to read it.

We trust our eyes, our sight, so much. Perhaps too much?

Today I heard a car pull into our driveway. My husband said, "Oh, here comes your friend."

Because of the circumstances, I was thinking only of friends of a particular group, and when I looked out the window and saw this woman walking towards our door,

I actually had no idea who she was. I didn't recognize her.

I didn't see her. I saw a stranger.

Once she got to the door and came in, and I heard her voice,

I knew exactly who it was, and when I saw her face, I saw her, not my ideas about her.

(She is a dear friend but not part of the group I had in mind, not what I expected.)

And so this painting, this Light of the Incarnation, has become a favorite of mine

because it is a reminder that I cannot see everything, know everything,

understand everything, explain everything.

A reminder that forces are at work that I will never know about.

That my life is part of a huge painting that I could never paint on my own.

And it is a beautiful, light-filled painting.

Painted by Carl Gutherz, a man who was born in Switzerland and lived part of his life in Memphis.

About the painting, he wrote,

"Up to the moment of the birth of Christ, the light of God came from heaven to earth--

but, God here, the light glows back from earth to heaven,

increasing in glory throughout the ages.

Beholding this, the heavenly host unite in rejoicing over the world redeemed."

(from Carl Gutherz: Poetic Vision and Academic Ideals, ed. Masler and Macini.)

Joy to the World!